What Makes a Manager Great? Maybe That’s the Wrong Question

Camille Hogg didn’t know what to expect when her manager scheduled her first growth conversation.

Other teams filed into glass-walled conference rooms with spreadsheets and skill matrices in hand, bracing for an hour of corporate box-checking.

Her manager, James, had something else in mind. He took each team member to a museum down the street from the office.

As they walked through the galleries, they talked. There were no slides or side Slack conversations, and no pressure to say the “right” thing. Rather, it was an open-ended conversation about Camille’s growth: what it could look like, where it might lead, and how to shape it together.

“It felt like he didn’t see growth as something restricted to office walls,” Camille told me. “I still think about it all the time.”

Years later, she still messages James for advice. “I still think of him as my manager,” she said, “even though I work for myself now.”

What stuck with Camille wasn't that the conversation ended with a structured development plan or well-earned promotion. She remembers the space her manager created and the care he showed.

She remembers the relationship they built.

What If Management Weren’t a Role, But a Relationship?

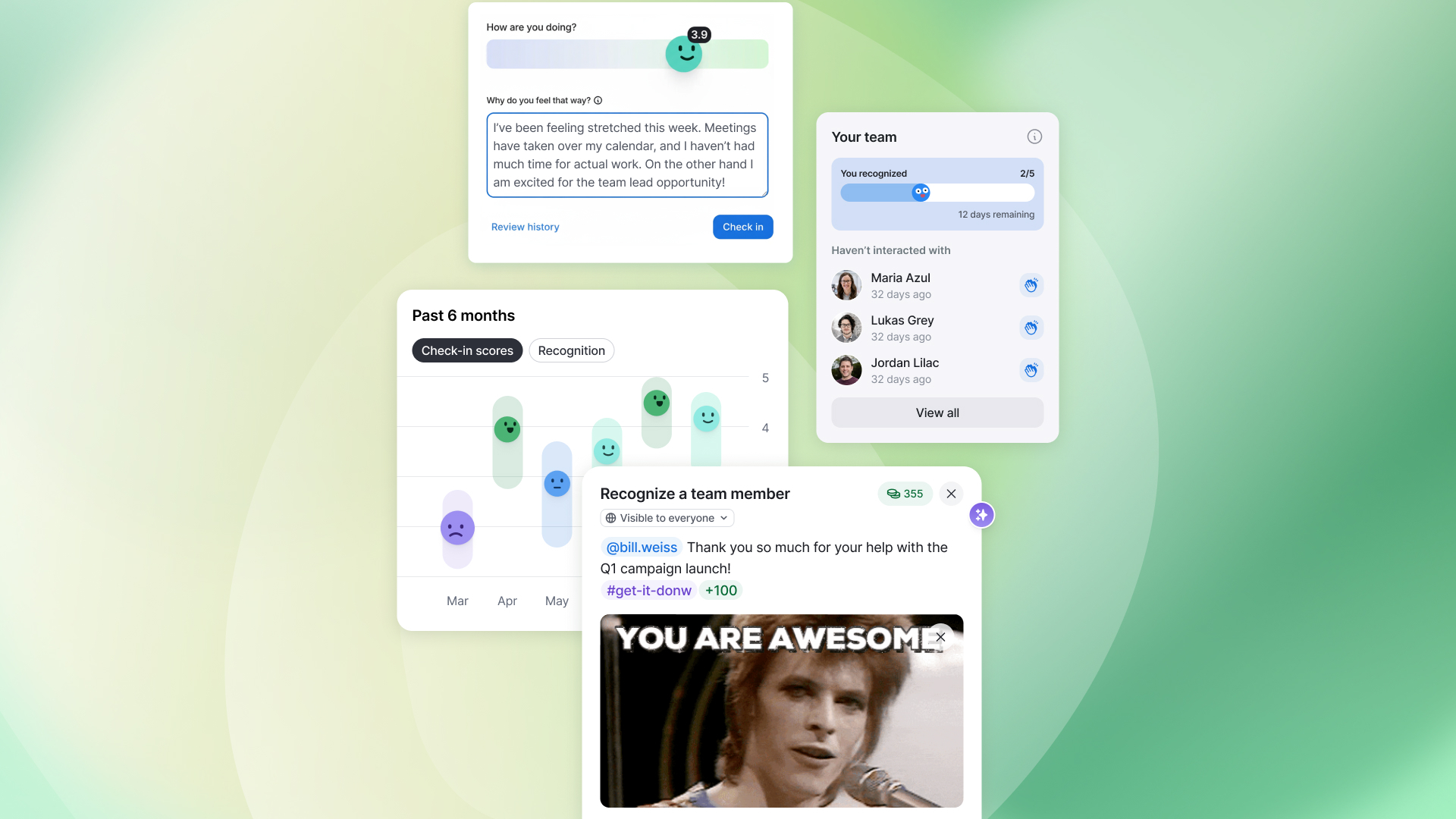

That story lingered with me. Not just because it’s a beautiful anecdote, but because it feels like the antidote to so many management experiences people share—stories filled with burnout, disconnection, and performative leadership. (When I reached out on LinkedIn for commentary on this article, someone warned me about the “faux-tivator.)

Embarking on this quest, I began with a single question: “What makes a good manager?” There’s a reason there are thousands of books on effective management; we’re all chasing the same question.

But what if it’s the wrong one?

I’ve come to believe it is. That question suggests a set of static traits, a personality profile, or maybe even a checklist you can follow to be a great manager. But managers aren’t algorithms, and people certainly aren’t identical inputs.

What I’ve learned from talking to a range of workers, from individual contributors and middle managers to directors, is this: Great management isn’t a persona. It’s a relationship.

Like any strong relationship, being a manager requires adaptability, presence, and care, qualities that often get lost in the haze of meetings and metrics.

Talent and performance leader, Matt Gentry, put it well:

“Goodness is not a binary. It’s a direction you're heading in, rather than a destination. As a manager, I'm still on that journey every single day.”

The stories that follow aren't about management superpowers. They're about real people wrestling with the messy, human work of building relationships while getting the work done.

The Accidental Manager

Andie Rosendin didn’t raise her hand to be a manager.

“I knew how to do my job,” she said. “I understood my role. But then my manager said, ‘You’ve got what it takes to be a people leader.’ I remember thinking, ‘I don’t know if I want to do that.’”

Despite her hesitation, she was encouraged—even pressured—to take the leap. Her manager was someone she respected, so she did.

But it soon became overwhelming.

“I was trying to support my sales team the best I could, but it was a high-turnover department. There were long nights; sometimes we were working until 2 a.m. It was exhausting.”

She remembers asking her manager for a change: Could she step down? Could she try something that aligned better with her strengths?

“I wanted to stay. But I didn’t feel like I was serving well as a leader—and I didn’t think the team was thriving the way they could,” she said. But Andie said there wasn't a way to step back. She asked about other roles that better fit her skillset, but was encouraged to endure.

Eventually, Andie left.

Her decision went deeper than simply being burned out. It was the disconnect between her unique strengths and the role.

Andie’s experience is far from unique. According to research from the Chartered Management Institute, over 80% of managers are what the industry calls “accidental managers.” These managers didn’t actively pursue a path into leadership. Instead, they were promoted because it was the only viable path for advancement—or because business needs made themselves known.

This accidental management phenomenon is a major reason many managers feel overwhelmed and unsupported today. Only 44% of frontline managers say they feel equipped by their organizations to lead, and nearly 60% report higher emotional demands than their direct reports. Given these challenges, it's not surprising that nearly half of middle managers consider quitting within the year due to unsustainable stress.

“Most people think of ‘up’ as the next thing for them to do because it means more money, more status,” said Mike Randolph, a leadership coach I spoke with. “Not everybody wants to do that, but that’s the default path.”

What Promotions Leave Behind

Promotion doesn’t just mean leading a team. For many, it also means keeping your old job while picking up the emotional weight of a new one.

Many managers are quietly navigating another role: the player-coach. This role involves someone who’s expected to lead a team and continue executing as an individual contributor. There’s no reduction in workload and sometimes no bump in pay or title, either.

After moving on from that sales role and dedicating her career to HR, Andie found herself in that player-coach role.

“I was managing a team while still doing the same job I had before,” she said. “Nothing was taken off my plate.”

Mike validated her experience:

“That’s the hard part with a lot of managers—they have their own bodies of work along with all of the people management that they have to do.”

When that’s the setup, no wonder two-thirds of managers report struggling with heavy workloads, with many holding more than 260 meetings a year. No wonder manager disengagement has reached a 10-year low.

If companies have player-coach roles, then, as Andie explained, those workers need strong support, infrastructure, and a clear path to identify their progression. "The goal is to eventually move out of the IC aspects of the role and focus on the growth and development of their team," she said.

Management Can’t Be a Copy/Paste

Ask ten people what makes a great manager and you’ll get ten different answers. And that’s the point.

Camille put it plainly:

“You can’t copy and paste leadership. The best managers adapt to the team they’ve got.”

This sentiment came up repeatedly in my interviews. The best managers weren’t the most experienced or extroverted. Instead, they truly got to know their direct reports and figured out the best way to optimize their strengths.

As Andie explained it:

“My last manager really listened to what brought me joy. She quietly observed what I was good at and encouraged me to lean into it—that’s how I ended up getting accredited and leading work that aligned with my strengths.”

This personalized approach requires managers to be comfortable in their own skin first. Authenticity matters; you can't truly see others if you're busy pretending to be someone you're not.

That’s why Mike tells his clients not to look for a generic “leadership style.” Instead, he encourages them to build a leadership identity—one that’s true to who they are and grounded in the needs of their team and company.

Leadership is contextual. He explains, “It has to align with your and your company’s values. Take empathy. It may be a crucial quality for a leader, yet what do you do when your organization doesn’t value it? You have to stay true to yourself and lead in a way that lets you sleep at night.”

That misalignment isn’t theoretical. When managers don’t feel they can be authentic at work but are stuck mimicking a version of leadership that doesn’t feel like them, their teams notice. Relationships suffer, and as a result, performance does, too.

Camille said the worst managers she’s had didn’t lack intelligence or experience. They lacked empathy and self-awareness. “It’s like they just swallowed a leadership book.”

Can You Care and Hit Your Numbers?

It's easy to idealize the relational side of management, but managers know the reality is more layered. They're responsible for outcomes, after all.

A manager has to support their team and deliver results. They juggle emotional labor and strategic execution, often while navigating power dynamics that make honest conversations difficult.

Camille described the role as "a conduit between the employee and the organization." Her best manager put his neck on the line to ensure the work was meaningful, even if it slowed delivery. "He'd always fight for us," she said, "even when it made his life harder."

This balancing act distinguishes exceptional management. The best managers create the conditions for psychological safety and high performance. When this balance is off, it breeds disengaged and even toxic cultures. When done well, it transforms workplaces.

Organizations that treat management as merely a technical role miss this critical dynamic. The best companies know that when managers build strong, trusting relationships, their teams perform better. Employees are more engaged and more likely to go above and beyond when they know their manager has their back.

That’s why companies that understand the true nature of management invest in their managers' relationship-building capabilities as seriously as they do technical skills. A good relationship isn't a bonus. It's quite literally the job.

Rethinking the Ladder

Many professionals are increasingly aware that managing people isn’t the only path to impact.

After having my son, I stepped away from people management. I loved helping others grow, but I realized I couldn’t manage a team and a toddler and show up well for both. Moving into an IC role felt like a return to myself, not a step back.

Several companies are stepping up and recognizing the need for distinct growth tracks for individual contributors. For example, organizations like Shopify and Microsoft have dual-track systems to ensure ICs can advance without transitioning into people management roles. Despite this, the culture around IC growth tracks is inconsistent at best; most organizations still rely on traditional promotion practices that prioritize managerial roles as the primary path for career advancement.

But some of the most effective employees choose not to climb—and perhaps that must be normalized. For technical professionals, this might mean becoming a specialist rather than a manager, deepening expertise in a specific domain. For others, lateral moves across departments can provide new challenges without the burden of overseeing a team.

There should be room for people to lead without needing to manage, grow without needing direct reports, and make an impact without having unrealistic job expectations.

In other words, just as we need to rethink what growth looks like for individual contributors, we need to reimagine what support looks like for the people tasked with leading them. If we're serious about building better workplaces, we can’t treat management as a default path or a personality type. Great management is a relationship worth investing in.

A Better Question

So maybe the question isn’t, “What makes a good manager?” Perhaps it’s: Are we creating the conditions for great relationships between managers and their teams?

More specifically, are we setting managers up to lead successfully? Are we valuing the emotional labor that management requires? Are we recognizing that not everyone wants to—or should—manage people?

The best managers aren’t superhuman. They’re just human, and in the best of ways. They care, listen, and adapt. And they build relationships that outlast titles and transitions.

And that’s what makes the work matter. Because when your manager cares about you, you care about the work.

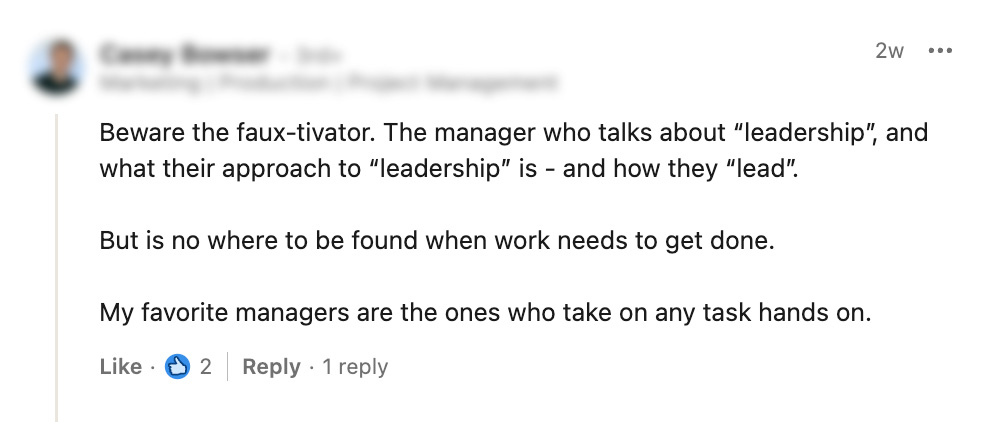

Wondering where to start? Download the Manager Playbook to build a better systems for managers and teams alike.