An Internal Note to Bonusly Engineering: 2025 in Review

Hello Bonusly.

I wanted to look back at what the Product Org did in 2025. There’s an undercurrent of altruism in Tech (open source being a good example). So I decided to share it with you publicly as I think other companies might benefit from these examples as a point of comparison when making decisions about how to operate.

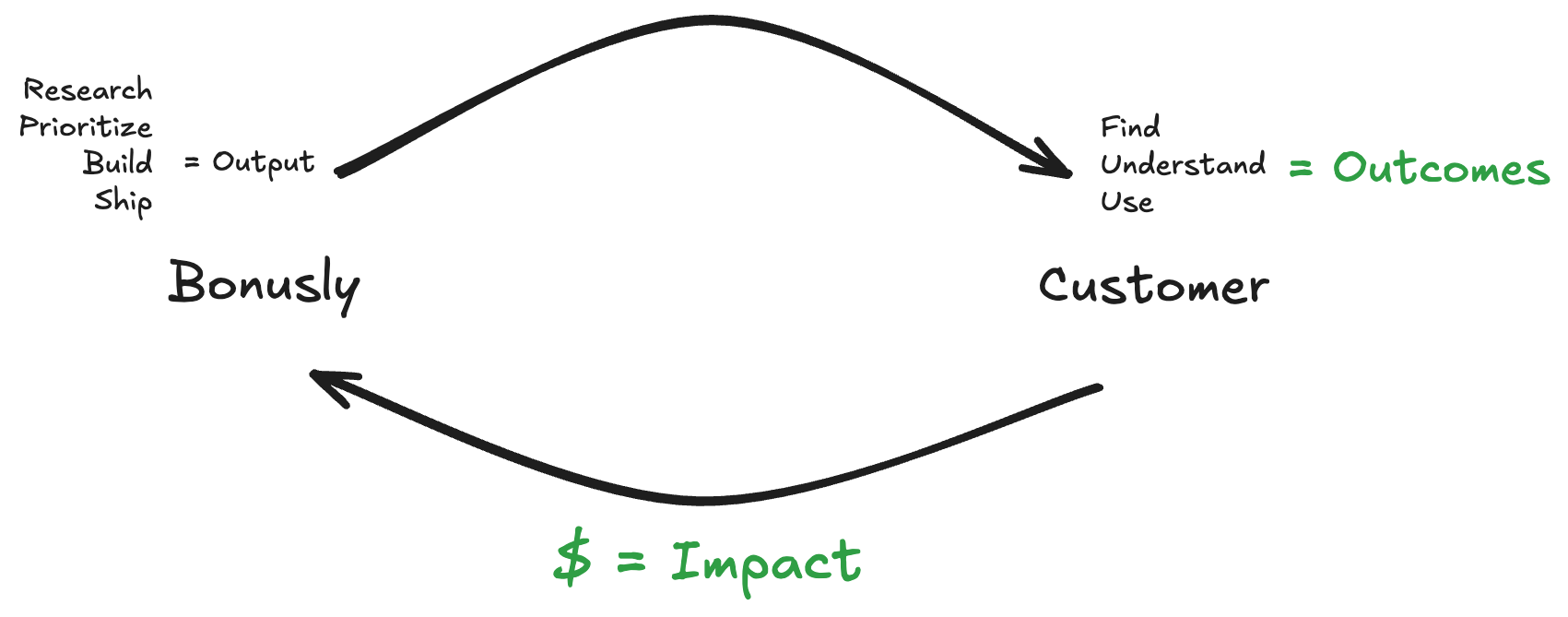

Our job, here in the Product Org, is to help drive customer outcomes and business impact; basically everything in green here:

I don’t care if we write the most elegant code or create intuitive UX if customers don’t use what we ship. This is why outcomes and impact carry outsize weight when we think about what good performance looks like at Bonusly (blog).

But it’s also true that we don’t get outcomes or impact without output. So I thought I’d look back at our output in 2025, as I think it was an instructive year.

(+): What I’m proud of

(+/-): Where I have mixed feelings

(-): What didn’t go well

(+) We got serious about using AI to be more productive.

I had a lunch meeting with an engineering leader I respect in March. And she asked me if I had tried Cursor yet. “No,” was my response. “But I’ve heard about it. What do you think?”

“Game changer,” she said.

So after lunch I went back to my desk, downloaded it and started to use it. It turns out others in Engineering had been doing the same. We shared notes, started showing it off, and after that, AI usage took off here like wildfire.

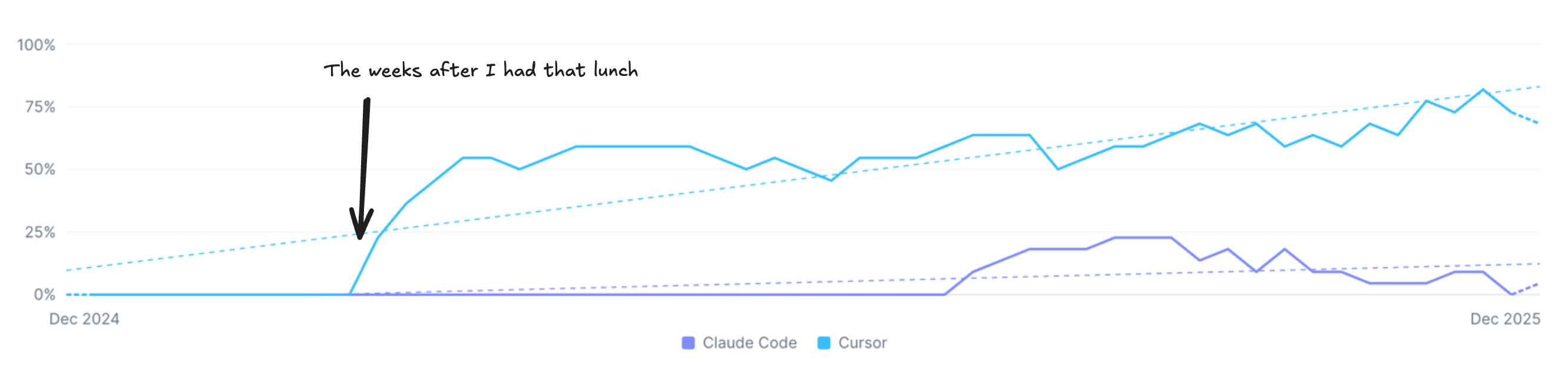

This graph shows us the % of people who write code here that uses AI to do it. And it’s not just engineers. Designers and PMs are in on this too creating prototypes, submitting PRs, and jamming.

Importantly, we decided at the executive level to make AI dead simple for people to get their hands on. We give everyone who wants it a Cursor and Claude Code license, and we give them what is effectively unbounded access to the most expensive models. Many of us are coding on “max mode” in Cursor most of the time, with Opus 4.5 being a recent favorite.

It’s wild.

But I think the way each of us uses it is divergent. Some people write PRDs and don’t code anymore. Not really. Others are just using tab completions. And we’re not at 100% utilization, which means some code contributors aren’t using it at all.

AI usage does not yet equate to the high PR throughput.

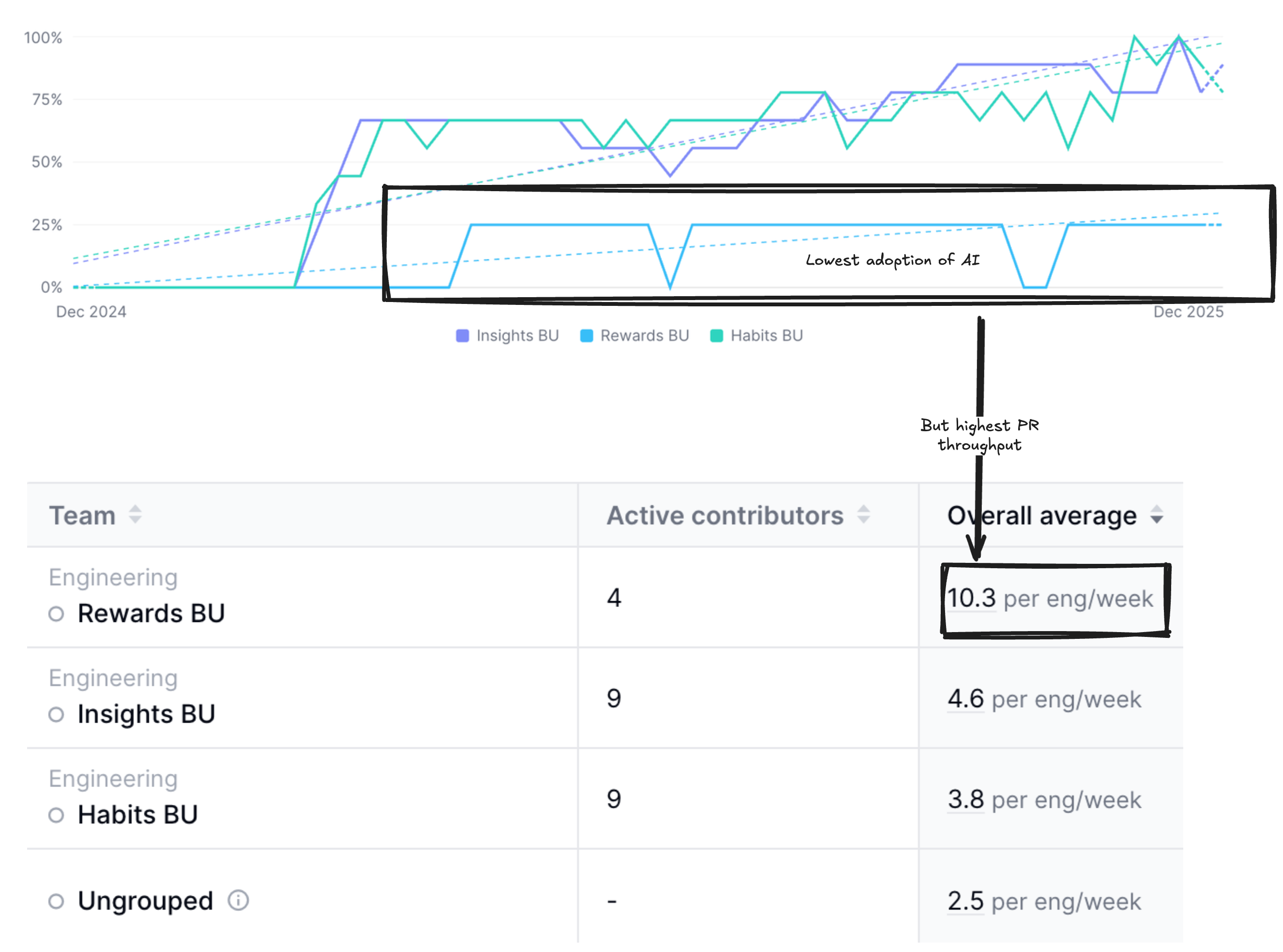

When we plot AI usage by team, we see a curious pattern emerge. Our engineering teams are divided into business units (BUs). We have three. Check out the Rewards BU team’s AI utilization (light blue):

The engineers on our Rewards BU have the lowest AI adoption rate by a mile. But they also have the highest PR throughput rate, by a mile. And these numbers defeat the idea that AI instantly gives engineers “super productivity.”

We’ve not yet arrived at the point here at Bonusly where AI has truly transformed how we work. I’m interested in figuring out how to remedy that. I’m observing a diminishing amount of “slop” produced by AI coding agents (especially with newer reasoning models), and an increasing amount of well-structured code. Problem definition, not solution execution, is becoming the bottleneck. So perhaps the future of Engineering lies in problem definition?

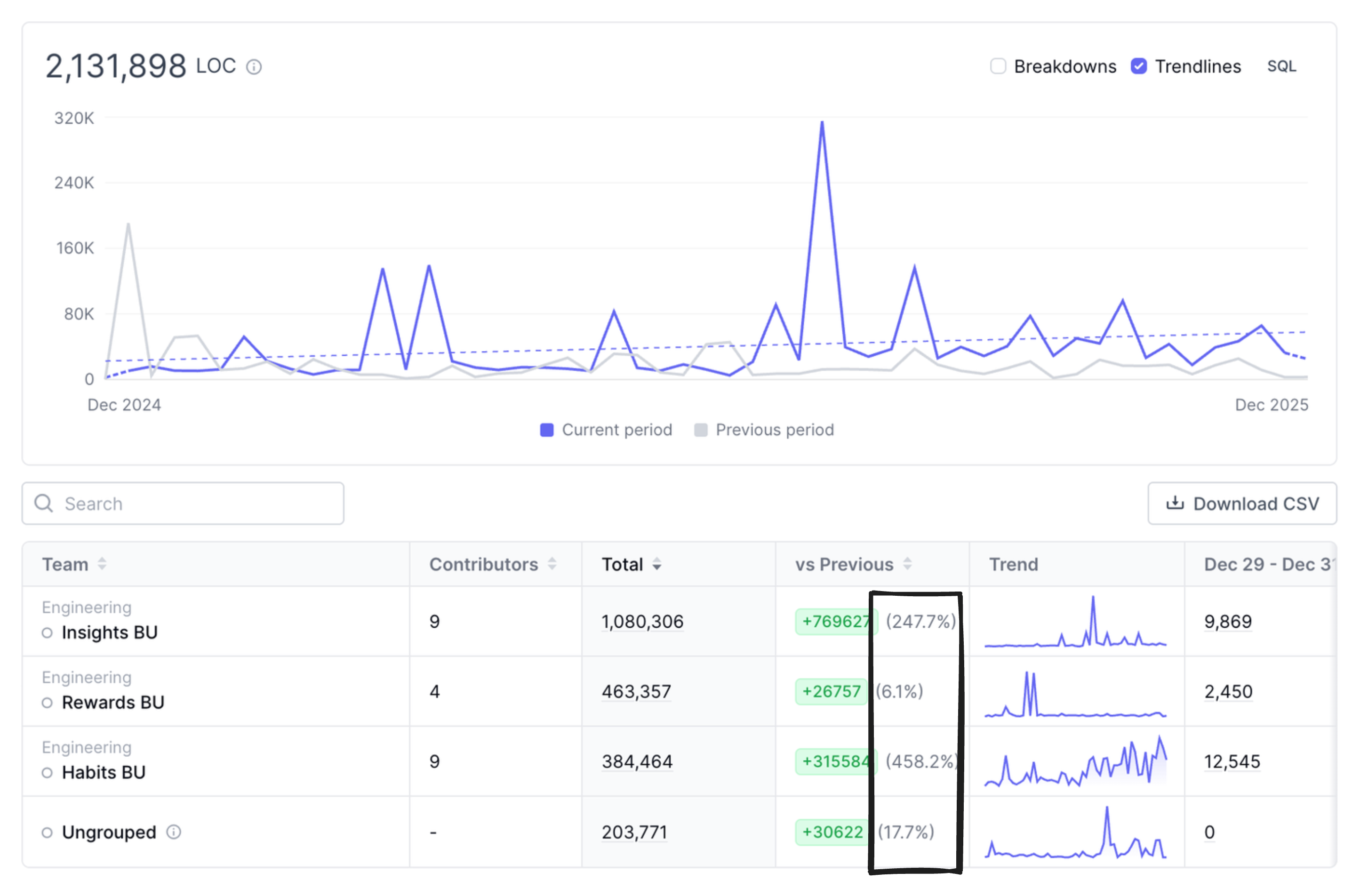

(+/-) We changed a lot more code in 2025 than in 2024.

Our headcount numbers in 2025 were relatively consistent with 2024. At least, they were consistent enough not to explain this massive delta in lines-of-code changes year-over-year.

The purple line in the graph is 2025, and grey is 2024. And this number includes additions and subtractions (removing code is also progress).

So perhaps this is where AI does show up as being impactful. PR throughput was only about 3% higher year-over year; our PRs are way too big. Code review is still done by humans here at Bonusly, and large PRs are much harder to review. Large change-sets are also riskier for Production systems. It's harder to to figure out what caused a regression when you introduce 200 lines of new code at once than it is when you introduce 20. From my perspective, AI doesn’t make it ok to have large PRs; I’m still in the make-them-smaller camp.

We have some work to do here.

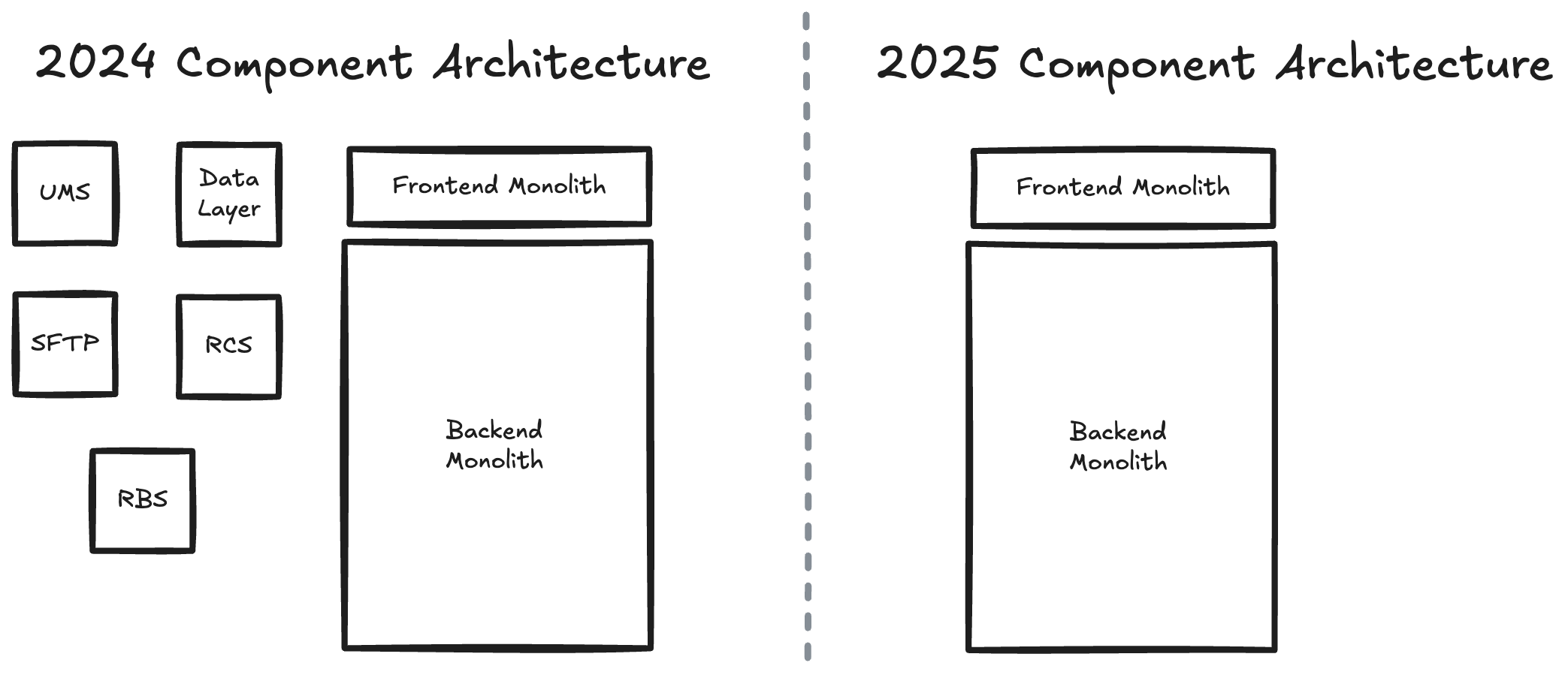

(+) We finished pulling every distributed service back into the Monolith.

We entered 2024 running a set of distributed services to serve the product. Some were developed on the JEE stack. Some in Go. Some in Python. And some in Ruby. The idea was teams could develop software quickly, in their language of choice, without having to manage the complexity of our convoluted Monolith (featuring Ruby on Rails, Jquery, CoffeeScript, etc.). And we’d get the scaling benefits of running distributed services.

Most of our mental energy was focused on those services.

But most of the business ran through the Monolith. And this created an inverted balance between where our engineering mindshare was focused, and where the business was focused. We found that scaling issues were related to design decisions that would affect any stack, and not to Ruby on Rails. I wanted all of our cognitive energy focused on improving the part of our software that actually ran most of the business.

So we embarked, in 2024, to pull all our services back into the Monolith. This meant re-writing most of them into Ruby (AI was massively helpful with this) and punching holes through firewalls for database connectivity.

We finished the work in Q1’25, and it made the whole system much easier to reason about since everything was now in one place. We’ve seen a corresponding reduction to our Large-Scale Incident (LSI or P0) rate since the cutover, too, which is a win for our customers.

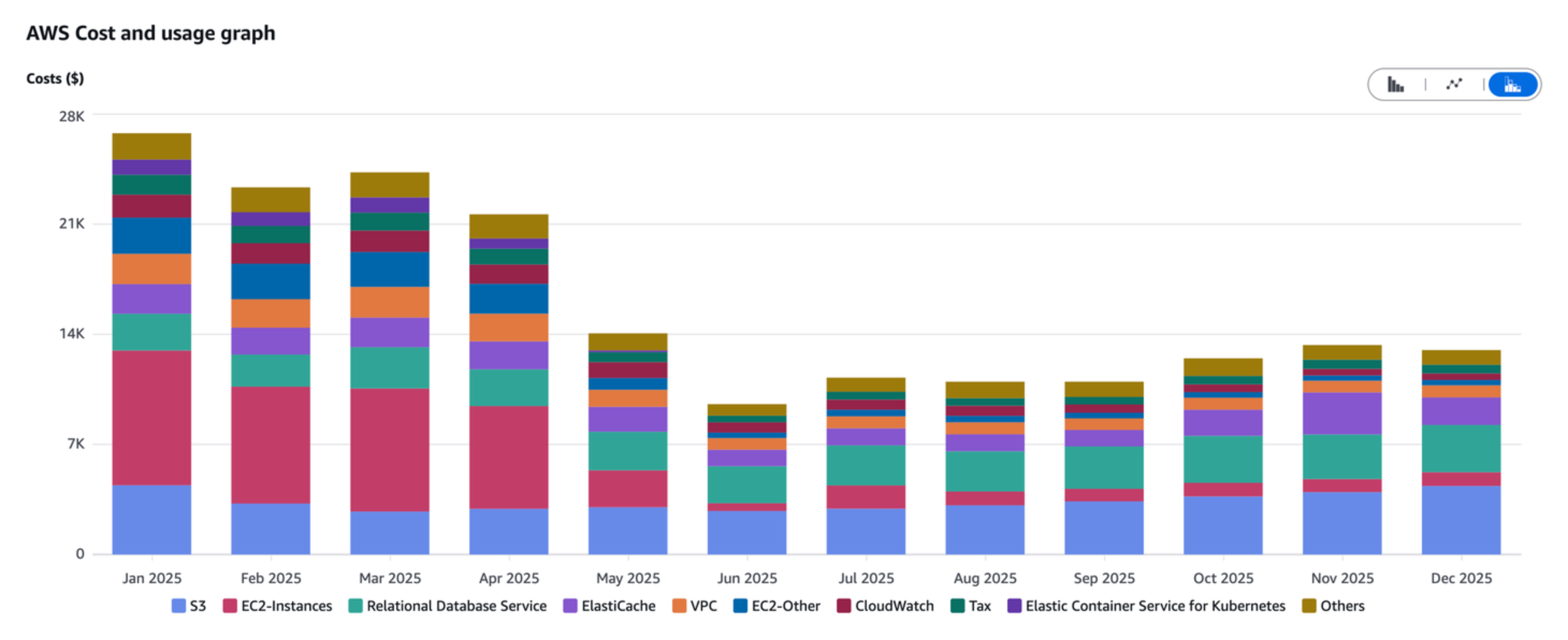

(+) We consolidated our move to Heroku.

With everything in the Monolith we were positioned to tear down most of our AWS infrastructure. Everything became a hell of a lot simpler. And yes, we moved a fourteen-year-old business from a self-managed, K8s-based infrastructure on AWS back to Heroku. This is the opposite of what most companies do as they scale.

Our AWS costs came way down. Yes, Heroku was a new cost, but all-in our infrastructure became about 40% cheaper with the addition of Heroku than it was before.

Here’s the delta in AWS costs (Jan’25 was emblematic of what we paid each month in 2024):

We’re not going to win, as a business, because we’re good at CloudOps. We’re going to win because we help people build habits that make them better teammates. This move also reduced the size of our dedicated CloudOps team from 2 to 0.5, where our remaining CloudOps engineer is also writing application code. That puts more of Engineering on the core problem, which is, I think, the right tradeoff.

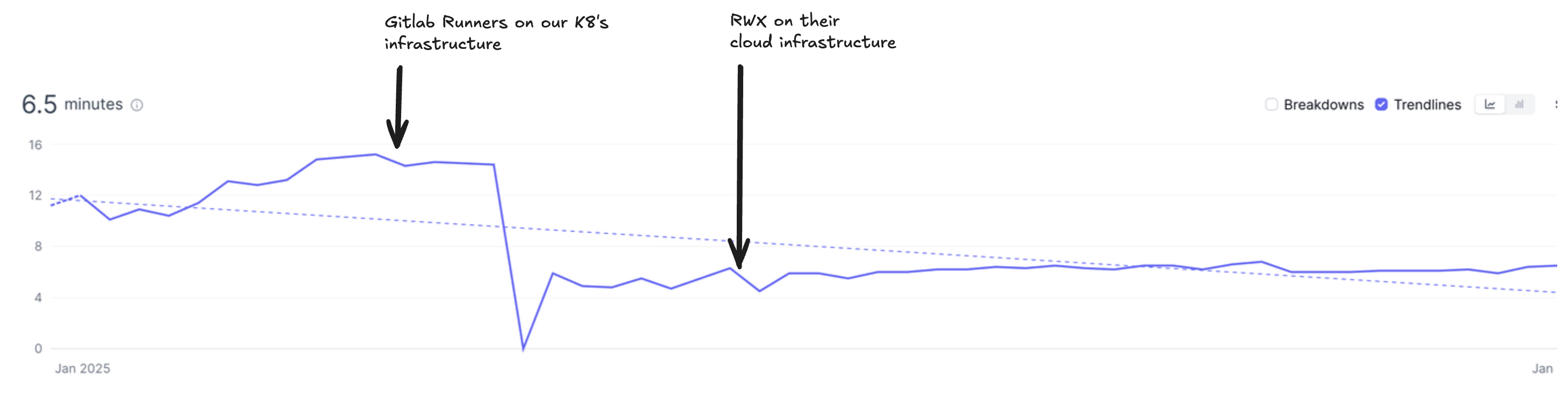

(+) CI/CD got a lot faster.

Simplifying our Production infrastructure gave us the opportunity to simplify our CI/CD process, too. CI/CD stands for Continuous Integration/Continuous deployment. It's basically a process we use to verify our software's quality and ship changes to our customers. In 2024, we used Gitlab for source control. And we used self-hosted Gitlab Runners for CI/CD. We found our setup to be error-prone, slow, and expensive.

In a DX survey, one engineer said:

“These systems aren't given the priority they need. Multiple incidents have been alerted, identified, and fixed; only to then stall while the deployment process churns for 40 minutes.”

And another said:

“We need to make deploying to Production really, insanely fast. This will give us confidence that, if we make mistakes, we can fix them now.”

We decided to overhaul our CI/CD system. And to set ourselves up for that, we migrated from Gitlab back to Github as we’d been wanting to make that change anyway (better UX), and we observed more CI/CD vendor compatibility with Github. We then went shopping for a new CI/CD vendor and landed on RWX, a new company that has been remarkably attentive to us, and that has the fastest CI/CD process I’ve seen.

In 2025, CI/CD became 260% faster than it was in 2024. This gives engineers that their code changes will get in front of customers quickly. This is especially important when moving fast. If we introduce a bug, we want to know we can have it fixed in minutes. Knowing that reduces fear, and less fear gives us more speed.

Engineering sentiment shifted dramatically after rolling out RWX in May:

“CI is going way faster. This is a game changer. My next request instant rollbacks. :)”

And

“Early, but I'm so much better than before! I feel I can deploy code reliably without babysitting my PR's which is a huge cognitive win.”

(-) I failed to launch ShapeUp for a second time in my career.

We changed how product engineering works in 2024 and made a big improvement to velocity (blog). And that unveiled a new set of bottlenecks, namely:

- Product Design can’t get far enough ahead of Engineering.

- Software updates are so frequent and widespread that our CS, Sales, and Marketing teams often don’t know about them, which denies us opportune GTM moments and puts us in a reactive mode when customers have issues related to them.

- Internal product communication is constant and overwhelming. It’s hard to know what’s happening and when.

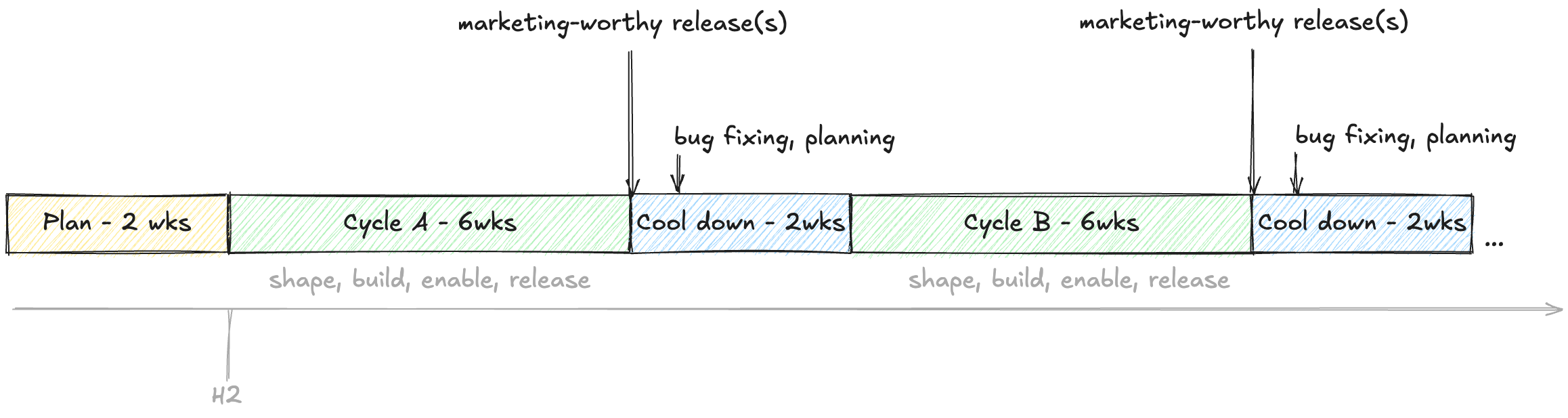

We needed to find a way to attain high velocity, but now at the company level. And my hypothesis was we could do that by aligning the company’s cadence on product-release cycles. Shape Up is a software-development methodology popularized by 37 Signals (or are they called “Basecamp”? I can’t ever remember). The methodology advocates working in six-week cycles with a subsequent two-week cooldown. All work is started and shipped within the cycle. And the cooldown period is a time to breathe and plan what’s next.

Team composition matters here, too. Shape Up wants small, autonomous teams working together each cycle. We already had pods, so the small-teams thing was already organizationally there. But we also added GTM people to teams. The idea was that the dedicated GTM member for each team would carry the responsibility for enabling the GTM org. Being dedicated would mean they’d have intimate knowledge of the team’s projects, and would have even helped shape the work at inception.

I did a ton of campaigning and convinced people that Shape Up could address our bottleneck issue. And together, we ran a month-long change-management campaign to re-organize the company around it.

We only made it through two cycles. What happened when I did this at Gusto happened again here:

- Engineering velocity tanked. Our units of work were actually much larger via Shape Up than they were before it. This meant fewer, larger releases.

- Work spilled into the Cooldown for every team.

- “Shaping,” that is the process of creating pitches (PRDs), is actually an onerous process and creates a lot of waste. People pour energy into shaping projects that never make it past the betting table. And that sucks.

- There was pressure to “sneak in” extra work into each cycle; a bug fix here, a small feature there.

- GTM coordination did not improve. Dedicated members found it nearly impossible to stay on top of projects as they had other GTM responsibilities to attend to. The best coordination system was still a monolithic one, which is what we had before Shape Up anyway.

So, here we had lower engineering velocity and the same bottlenecks we had before. After two cycles, we abandoned ShapeUp in favor of a much more efficient BU structure and a push toward a “generalist” mindset in how we work, which we’ll cover some other time.

(Also, note to self: 37 Signals doesn’t have a Sales or Account Management team. Their constraints are much different than ours.)

If we do the math, we see more + than - here. Chalk that up to a net positive year, I think. I expect 2026 to be another transformational year for us, especially in how our product takes shape. There’s so much opportunity.

Cheers,

JT

.png)